The only thing special he asked for was fresh lime juice, and I would squeeze it right in front of him.

DE: Did he tip you generously?

RG: It might have been three or four dollars, or something like that—kind of average. Nothing like a twenty or anything bigger. And I wasn’t expecting it, or think I would be getting something more just because of who he was; and didn’t even think about it in that way. Really, if you're looking for a big tip, serve mobsters!

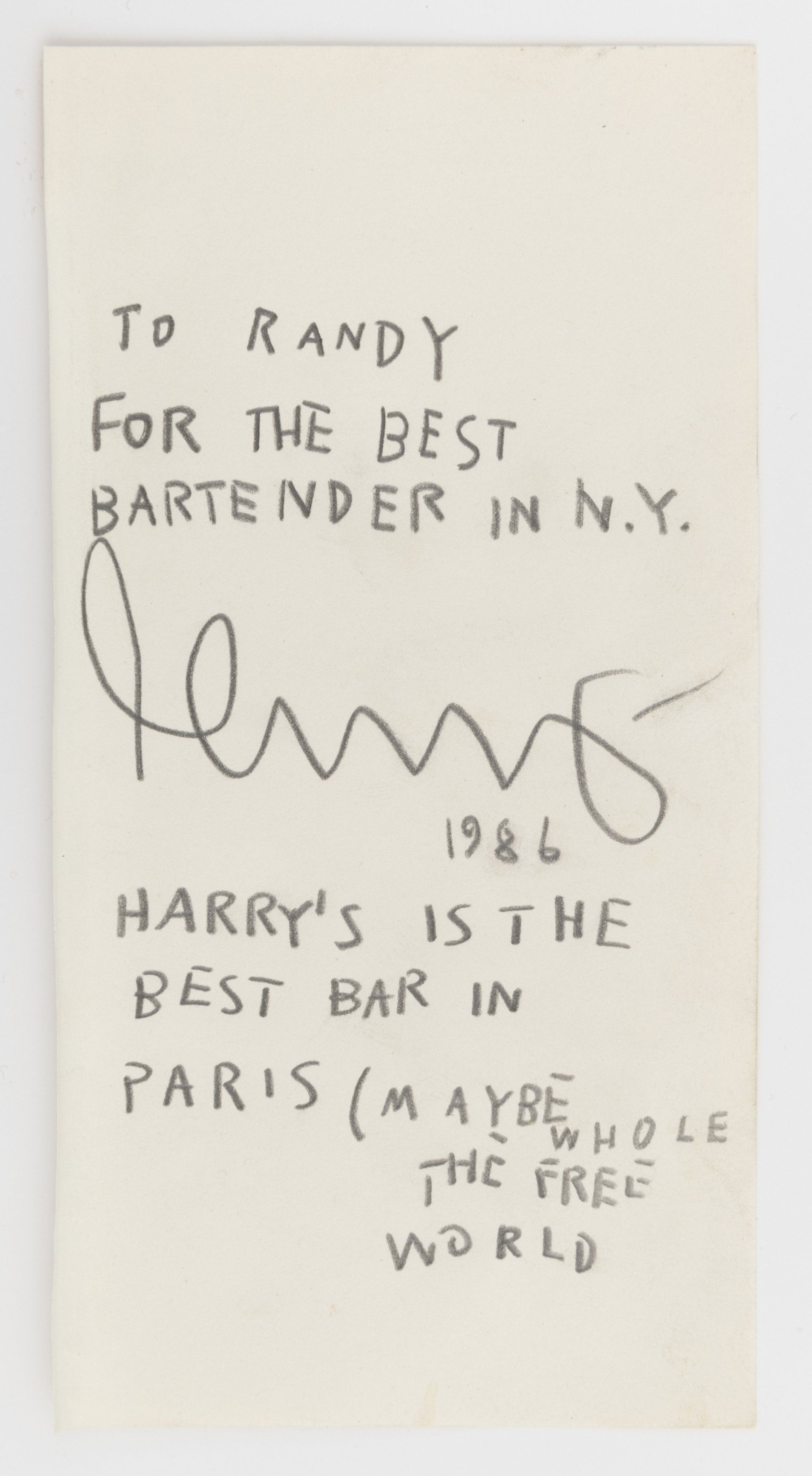

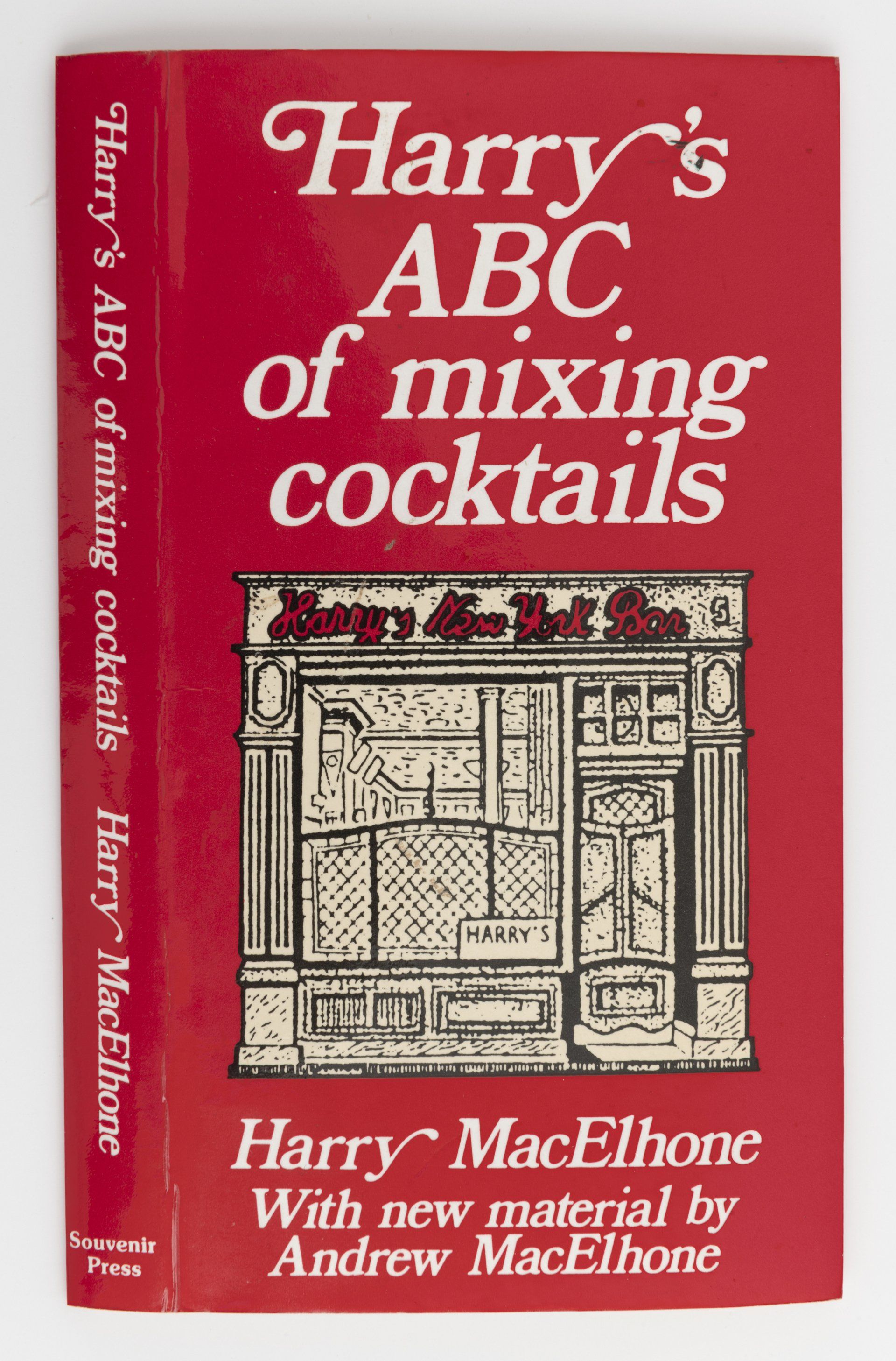

DE: Did Jean-Michel come into the bar one day with Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails for you, or how did that come about?

RG: Well, he would disappear for a while. He would talk about going away on trips—to Europe for one of his art shows or travelling to Hawaii, places to dry out. I know he’d go to some warm place, and he’d come back looking halfway healthy and off drugs. He’d probably go and score later that day. I had just stopped using myself for a few months at that point. I knew the pain he was experiencing if he was trying unsuccessfully to stop. I tried to put a bug in his ear. That there was relief if he wanted it. I’d mention to him, “You know what, Jean-Michel, you don’t have to live this way.” There were people we knew mutually who stopped using. His response was, “Well that works for them, but not for me.” That he came back to visit at the bar after I encouraged him to stop drugging is a testament to his being open to the possibility of change at that time. I know when I was using I was in no mood for listening to anybody who wasn’t drinking or drugging. So really it was a surprise that he would return to visit.